How can we test whether a hedge fund programme is adding value to large institutional investor portfolios? This question has grown in importance since the financial crisis, as an eight-year equity bull market has made hedging unattractive. Frequently, hedge fund programmes are compared to the asset class they most resemble (for example, a hedge fund programme is sometimes compared to a long-only equity index, such as the MSCI All Country World Index). In this context, the performance of many hedge fund managers has lagged significantly since 2009. Given that hedge funds may have lower market exposures than a long-only equity benchmark, is this fair? If not, how should they be measured? We argue that a beta-matched mix of stocks and bonds is the most appropriate measuring stick for customized hedge fund programmes, as it compares them to the risk profile that investors could achieve using traditional markets.

Determining the appropriate benchmark mix

To determine the appropriate mix of stocks and bonds to use in comparison with a hedge fund programme, first consider its long-term equity beta. While the beta exposure can vary from one year to the next, over a reasonable three-to-five year evaluation period, the beta of most diversified programmes does not vary greatly.

The equity beta of a hedge fund measures the sensitivity of the hedge fund to changes in the equity market. As such, it is a good approximation for the level of equity-like returns that we can expect from the hedge fund. The difference between these expected returns and the portfolio’s actual return is the fund’s “alpha”. Since investors can replicate a hedge fund’s beta by allocating to stocks and bonds, a good benchmark for evaluating a hedge fund allocation is a mix of stocks and bonds in which the allocation to stocks is based on the beta of the underlying hedge funds. For example, an investor could allocate to a hedge fund programme with a beta of 0.40 to equities, or to a portfolio of 40% equities and 60% bonds, and achieve a very similar level of equity risk. Therefore, a 40/60 equity/bond index could be used to evaluate a portfolio of hedge funds with an equity beta of 0.4.

Bonds comprise only 60% of the evaluation index, but alpha is earned on 100% of the hedge fund portfolio. As a result, hedge fund alpha only has to be greater than 60% of bond returns over time in order for the hedge funds to be additive versus the traditional portfolio.

How to apply this framework in asset allocation to improve absolute returns

Investors that have funded hedge funds entirely out of their equity sleeves will systematically earn less equity market return than their benchmark. That said, there is a way for investors to implement hedge funds programmes such that they can outperform their benchmark on an absolute basis. First, investors shoulddetermine the desired equity exposure for their overall portfolio. Then, they should determine their tolerance for hedge funds, including liquidity and tracking error constraints. Finally, they should substitute equity and bond exposures with hedge fund exposures, using X% from equities—where X is the equity beta of the hedge fund program—and having the balance come from fixed income. In the above example where the hedge fund beta was 0.4, 40% should be taken from equities, and 60% from bonds, to allocate to the hedge fund programme. This approach ensures that the equity beta of the portfolio is not diluted by the addition of hedge funds, which is important for investors trying to maximize absolute returns while comparing their overall portfolio to a static equity/bond benchmark.

Consider an investor that conducts an asset allocation study and decides to target 70% to equities and 30% to bonds. Investors may implement hedge funds in several different ways, each of which keeps beta-adjusted equity exposure at 70%. With a hedge fund beta of 0.4, investors could choose an equity/hedge fund/bond mix of 66/10/34 or 60/25/15 and still achieve a beta-adjusted equity exposure of 70%.

While hedge funds bring certain risk exposures to a portfolio, so do bonds. Interest rate duration risk from bonds may help mitigate short-term drawdowns but over the long term could be a drag on returns in a rising rate environment. For pension funds looking to construct a less volatile portfolio without too much interest rate exposure, an allocation to hedge funds could be an attractive solution.

Ramifications for today’s markets

Over multi-year horizons, the returns earned on a bond portfolio closely track its starting yield. Regardless of whether bonds are trending upward or downward, in years when aggregate yields are below 10%, bonds tend to earn their yield, plus or minus 1%. Given today’s yields, bond returns over the next five-to-seven years look relatively weak.

At the beginning of February 2017, the yield on the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index was 2.6%. Rounding this figure up to 3.0% to be conservative, and assuming a 0.4 beta for hedge funds, hedge funds have to produce 40% of equity returns plus 1.8% annually to beat a 40/60 equity/bond benchmark.

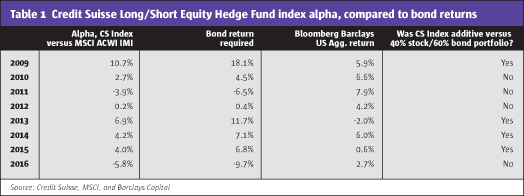

How does this 1.8% “required alpha” contrast with the historical experience of hedge funds? Using the Credit Suisse Long/Short Equity Hedge Fund Index, the alpha of this index over global equities on average has only been 1.65% annually since 2010.

However, consider that recent history includes one very difficult period, 2010-2012, when hedge fund returns were abnormally low and bonds earned far more than what was expected. From 2010 to 2012, the average 12-month alpha produced by the Credit Suisse Index was only 0.18% while the average 12-month return on bonds was 6.7%. In the following four years, from 2013 to 2016, the Credit Suisse Index saw average 12-month alpha of 2.75% – this is versus the average 12-month return on bonds, which was 2.5%. Alpha of 2.75% is nearly twice the 1.5% alpha required for hedge funds to beat a 40%/60% portfolio (as 2.5% return * 60% allocation = 1.5%).

The years 2010 and 2011 were difficult for many hedge fund managers; there were many that did not fully believe in the rally and were too quick to sell into fear, given the dramatic bear market they had recently witnessed. This period of negative alpha was nearly twice as long as the next-longest stretch in the early 2000s. If the last four years’ experience ends up being more typical of hedge fund performance going forward, bonds will need to earn 4.6% a year for a 40/60 equity/bond portfolio to beat the Credit Suisse Index.

Performance consistency

The alpha of a hedge fund programme may vary over time, and funds should not be excluded from investors’ portfolios simply due to recent underperformance. Some strategies have wider distributions of returns and can experience longer episodes of negative alpha relative to their more conservative peers. But if these strategies are uncorrelated and combined, the resulting diversified portfolio can create a more consistent alpha in the forward-looking environment that is compelling versus a traditional mix of stocks and bonds.

Summary

When evaluating the efficacy of a hedge fund portfolio, investors should consider what they can achieve in liquid, traditional markets, and focus should be on forward-looking measures. Weak forward-looking returns for bonds may make hedge funds more appealing diversifiers in the coming years. Investors can add value through hedge funds by funding them through the closest mix of stocks and bonds, and the alpha generated by hedge funds can translate into an improvement of absolute returns for investors.

- Explore Categories

- Commentary

- Event

- Manager Writes

- Opinion

- Profile

- Research

- Sponsored Statement

- Technical

Commentary

Issue 121

Hedge Fund Benchmarking and Absolute Returns

Testing whether hedge fund portfolios add value

JAMES FISHER AND DAN COVICH, ASSOCIATE DIRECTORS, PAVILION ALTERNATIVES GROUP

Originally published in the March 2017 issue